The pathology quadrilateral

Mapping our perverse trajectory from the present to the non-future

1.

In recent essays I have been exploring the idea, put forth by Mark Fisher and others, that we’ve reached a point in the development of capitalism that it is no longer possible to imagine a future. Or rather, this “no future” is a manifestation of the rapacious “need” that our current form of financial capitalism seems to “have” to reproduce itself, exactly as it is, forever and ever more. That is, capitalism has reached the point where it requires reproduction without natality.

A quick aside: the various manifestations of capitalism are institutions, and institutions (as I have argued) cannot themselves have “wants” and “needs.” However, those who are deeply involved in those institutions can become deeply indebted to the peculiar decision-making processes of those institutions (what I have suggested might be called “institutional rationality” as a good shorthand).

Most of these “needs” and “wants” that arise from our interactions with this market-financial behemoth are illusions. Money, for example, is a very effective illusion—it’s paper in your pocket or numbers on a screen, and yet the “presence” or “absence” of these factors can affect so many key aspects of human life. And, as it turns out, what capitalism really needs is not an actual future, but the constant illusion of a future:

People will invest in a better future if – and it is a very big if – there is a good chance that it will pay off, that the system reliably delivers that better future. Capitalism not only produces a society focused on the future, it requires it. If the promise of a better future starts to fade, a vicious cycle sets in. Why save? Why sacrifice? Why stick at education for longer? If doubt creeps in, people may work less, learn less, save less – and if they do that, growth will indeed slow, fulfilling their own prophecies. The biggest threat to capitalism is not socialism. It is pessimism.1

A succinct example of the “illusion of a future” is to be found in the current practices of recycling. As my friend Adam Kotsko recently posted on facebook, we are caught up in a space where the corporations that have created wasteful packaging and materials have offloaded the responsibility for ecological impact onto individual consumers. “Why aren’t companies responsible for the waste they generate? If recycling is so important, why aren’t products designed from the ground up to facilitate it? In fact, why are companies allowed to place recycling icons on materials that ARE NOT RECYCLABLE for all practical purposes?!”

It’s this last point that illustrates what I’m getting at here: I hold in my hand a bit of plastic, and stamped on that plastic is a recycling symbol. Supposedly, that means that this plastic item has “a future,” in that I can add it to the stream of recycled products and it will be melted down and turned into “something else,” other than simply being waste.

But as Kotsko points out, for almost all the plastic in our lives, as well as for many other items stamped with recycling symbols, this promise of a future is a simple lie. They will never “be” or “become” anything else, other than waste. Yet every time we interact with these items, we repeat (and reproduce) the mythology of sustainability that points toward some kind of open natal future, rather than a closed and fatal prolonging-of-the-present in place of a future.

2.

Recently I’ve been reading Carceral Capitalism, an amazing book by Jackie Wang. In the course of Wang’s analysis, she offers a reading of Rosa Luxemburg’s The Accumulation of Capital. There are two points in particular from Luxemburg that Wang notes:

Capitalism is inherently expansionary, as it seeks to realize an ever-increasing amount of surplus value, and

There is no reason why surplus value need be realized within the formal capitalist sphere when realization can be secured through violence, state force, colonization, militarism, war, the use of international credit to promote the interests of the hegemonies, the expropriation of indigenous land, predatory tariffs and taxes, hyper-exploitation, and the pilfering of the public purse2

What this means is that capitalism requires a border. That is, in the first and most basic analysis, capitalism needs a non-capitalist horizon in order into which it can continually expand. If capitalism becomes truly universal, it collapses.

This basic structure, however, is complicated by a second and equally-true situation: at present, capitalism has no rival. Especially since the collapse of the former Soviet Union and the Soviet Bloc in the early 1990s, capitalism is effectively ubiquitous. This means that there is no further territory into which capitalism can expand. It has no more borders to cross; it has reached its own horizon.

Following the logic of point 2 above, then, since the early 90s, the capitalist project has increasingly become a self-cannibalizing enterprise. The tactics and processes of repression and terror that for decades were outsourced and offshored through colonialism and imperialism have now come home to roost.

This seems undeniable at present, as we see armed gangs of masked federal agents, of dubious status and unclear organizational affiliation, become increasingly brazen in their willingness to harass, threaten, and even kidnap naturalized and home-born citizens in the name of “border security.”

That is to say, what was once a fixed border area has now become a mobile geography. Any area within the territorial United States can now be declared to be a “border,” allowing the continual (re)creation of a mobile and flexible “horizon,” beyond which the rule of law and the formal structures of due process no longer obtain.

How does this benefit the systems of capital? Well, this continual state of upheaval and destabilization de-territorializes (a term borrowed from Gilles Deleuze) the established and expected relations that are essential for feelings of peace and security. In this sense, capitalism creates the very sickness for which it will market itself to us as the cure. While remaining universal and unchallenged, this late form of capitalism has created a set of mobile and de-territorialized colonialist projects within itself.

3.

Not all of these re-constituted internal colonialist projects are physical arrangements. Some of them—often the most insidious and potent examples—are social in nature. That is, there are colonialist projects that function on the domestic level, creating horizons of division between domestic population groups, as well as between distinct individuals.

As the dissolution of the future becomes even more fine-grained, there is an eventual state of affairs where the colonial horizon interrupts our very concept of the self, leaving us instead in the state described by Felix Guattari and Gilles Deleuze, where we are no longer coherent individuals but rather as dividuals. In this fractured state, portions of our identity are separated and weaponized against other portions of our identity, leaving us continually in a state of existential disarray.

One of the ways that dividualization is weaponized against populations and against selves is through a strategic arrangement of time. Past, present, and future are deployed in a series of narratives that elicit maximum anxiety. Thus, “Are you saving enough for your retirement?” is a narrative that weaponizes the future against the present. “Are you living up to your potential?” weaponizes the past against the present. One of the earliest versions of this, of course, was the idea of “Keeping up with the Joneses,” which weaponized two or more contemporaneous present frames against each other.

In each of these cases, the result of this narrative weaponization is to destabilize our sense of safety and solidity in our present choices and social arrangements. We experience this destabilization at a micro level whenever we watch effective advertising. Suddenly we are aware of “problems” in our situation that did not exist before, and we feel a sudden hunger for a solution to these “problems” that only the targeted product can provide. What happens on a micro scale with advertising is also at work on a grand scale in our shared public sphere. Feelings of neighborliness and solidarity are suddenly upended and in their wake we are left feeling desperate for a simple “solution” that will return us to feelings of security and stability.

4.

As I have tried to think through these mechanisms of destabilization and social weaponization, I have developed a set of dyads that offer us four ways of thinking about the relation of the present to the future. In each of these four options, there is a cause for anxiety. Sometimes that cause is more apparent and clear cut, and at other times the relation might, at first glance, seem more benign. In each of the four cases, however, there is the possibility for a weaponized exploitation.

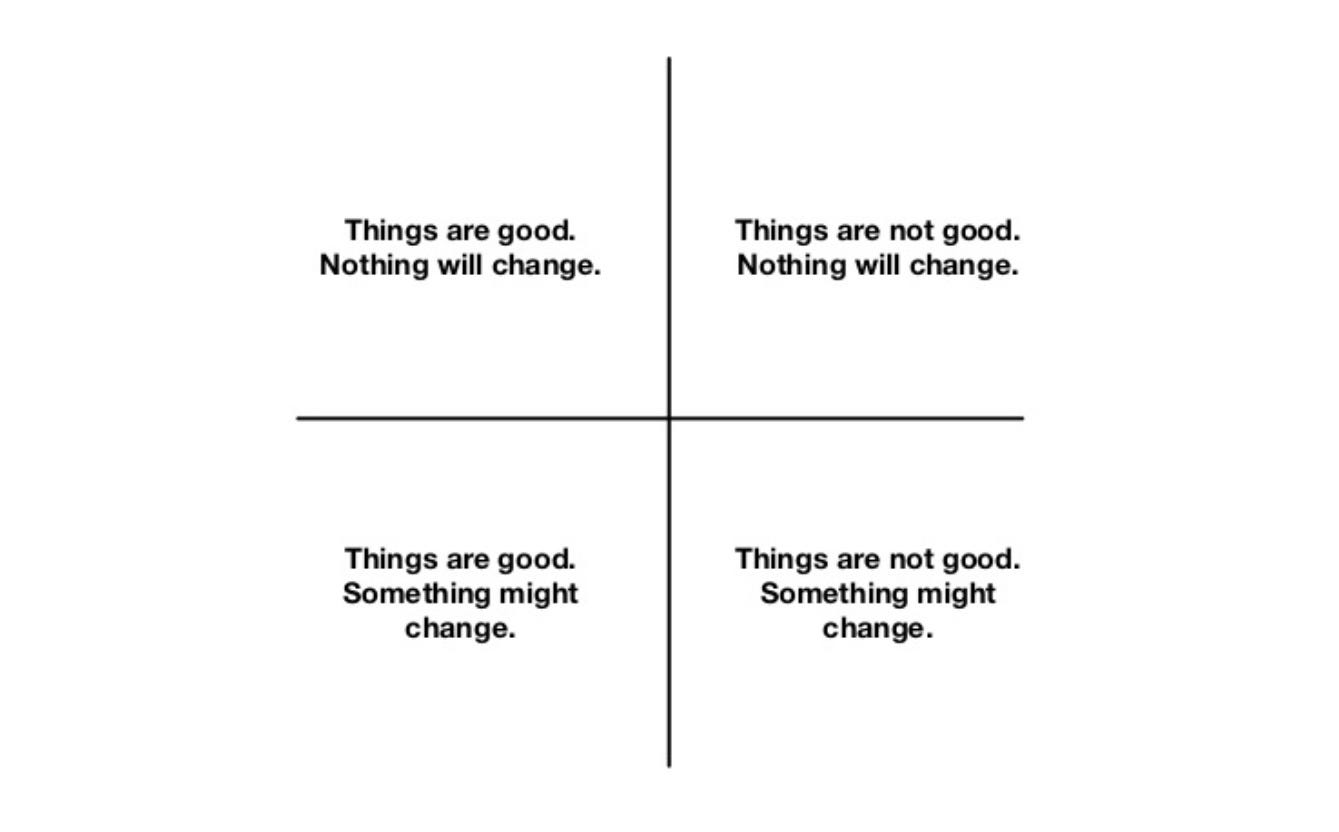

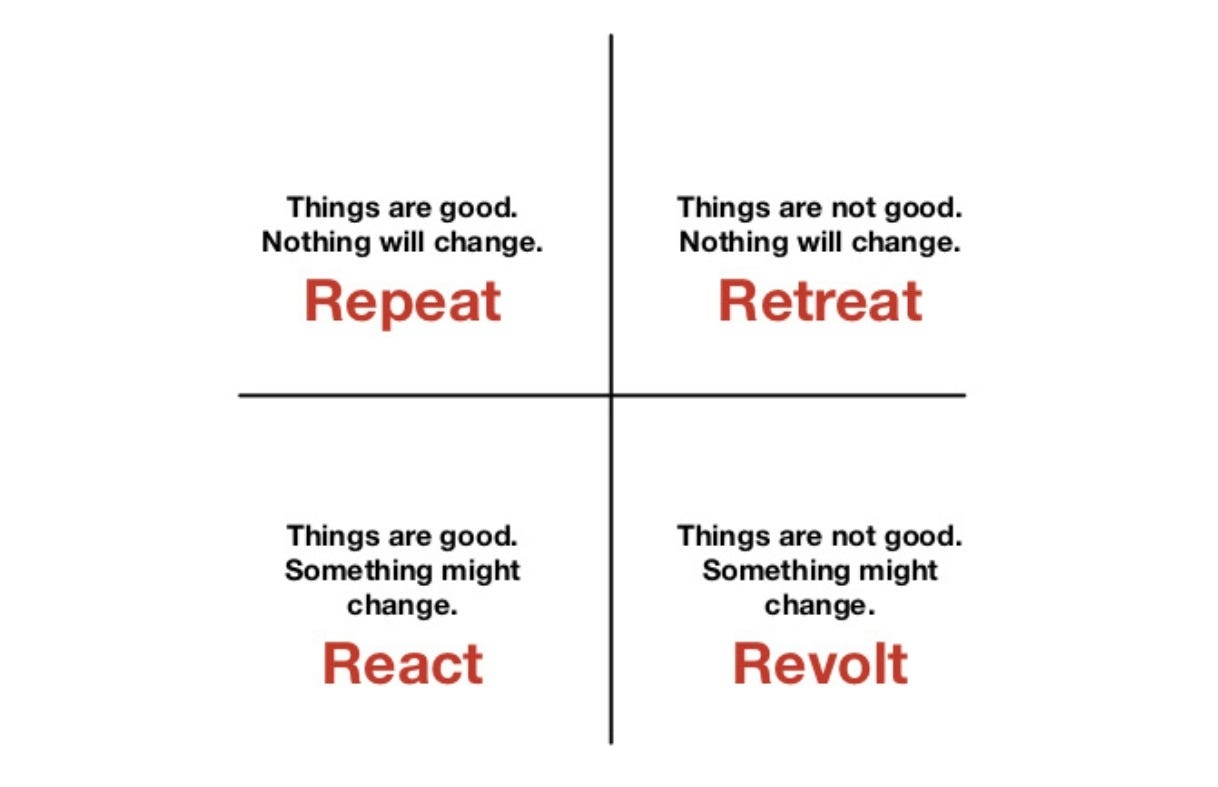

Arranged graphically, I refer to these four arrangements of present and future as the pathological quadrilateral:

The quadrilateral is a series of recombinations of two dyads:

Things are good, or, Things are not good, and

Nothing will change, or, Something might change

The phrasing here is chosen with some precision, in the sense that “Things are (not) good” functions as a phenomenological claim that feels like an ontological claim. In plain language, it is a dyad that offers me the opportunity to elevate my personal sentiments to a level of supposed objective truth. That is, I feel like things are not good, and therefore our public sphere is (objectively, concretely) not good.

This is not to diminish the value of an individual speaking about their own social location. Rather, we are exploring how such a valuabel act of self-confession might be weaponized to serve an interest other than the interests of the one reporting on their social location. Again, this is occurring in a realm of colonization. The interested parties here are not eliciting these narratives to create greater care for the vulnerable, but to excavate new markets that might be exploited for profit.

Even more than this, however, we are confounded by the second dyad. This dyad does not point toward the possibility of actual change (because, again, the capitalist paradigm is focused on continual re-production, without the possibility of actual natal change) but rather the phenomenological state where we feel as-if circumstances might or might not change. It’s a subtle but important difference.

5.

What interests me here is what we do with the affective residue that remains in the wake of these four narratives. At various points in our lives (and even in our weeks and days) we might cycle through each and every one of the four quadrants. Over time, however, we might find ourselves gravitating toward one quadrant in favor of the other three.

When this occurs, what results is a kind of sedimentation about the way the world fundamentally is, from this particular vantage point. That is, from a given quadrant, the world presents itself as a certain form of problem that might be solved by a certain form of action. So let’s examine these four responses, each in their turn.

The fundamental question in each quadrant is, “How are you thinking about the past and the future with regard to what actions you are taking (or not taking) in the present?”

When we feel things are good, and we feel like that state of affairs is relatively “safe,” in that nothing will change, then the natural desire is to lock that down. So we seek to repeat that state of affairs for as long as we can. We seek the repetition even if we learn that the continuance of our comfort is dependent on the suffering of others (that is, we resist becoming vegans because the burger tastes so good, despite knowing in some distant way that our enjoyment of the burger is dependent on the suffering of the cow).

In contrast, if we feel things are not good, but that there is no action that we might take that will change the not-good we are experiencing, the natural reaction might be to numb ourselves emotionally or chemically. In other words, we retreat as much as possible from the situation, hiding ourselves from the worst of the damage as much as we can. We get high, we dissociate, we engage in risky sexual behaviors, all to distract us from the trap we feel we are in.

Both of the upper two quadrants might be considered a more passive response to the given circumstances. We might characterize the upper half of the quadrilateral as a style of political aesthetics. Those who inhabit these quadrants do so with firm identity, rather than with irony. That is, they are really invested in the truth-state of the condition they feel (things are good / things are not good) as a kind of given reality, rather than a plastic circumstance. Those who find themselves in these two quadrants might add the phrase “and I deserve it” to their description of this state of affairs.

When we feel things are good, but we fear that something about that might change, then the natural response is to move to conserve the good we feel, and defend it against those perceived “enemies” who wish to take the good from us. Thus we might describe the action dictated by this quadrant as a reactionary posture. The task becomes building a stronger and higher wall against those perceived to be threats, and to imagine that God’s kingdom is a gated fortress. Shouting “Deus Vult,” we situate ourselves as defenders of the one, true faith.

When things are not good, but we sense the possibility that something might change, then we might naturally enter into a posture of revolution. We revolt against the status quo, the realms of injustice, or systems of violence. We revolt in the name of what we imagine might be improved. This quadrant is often where most of us would like to imagine ourselves: gallantly storming the ramparts and putting our shoulders to the wheel, we do our all to move the world in the direction of “progress.”

Thus the lower two quadrants might be considered a more active response to the given circumstances. We might characterize the lower half of the quadrilateral as a style of aesthetic politics. Those who inhabit this lower half might find themselves experiencing a more flexible, ironic sense of identity. Despite being serious, they are not above doing public actions for the “lulz.” They are really invested in their response to the state of affairs in which they find themselves, even as they find all the factors of circumstance and identity to be more variable and fluid. Those who find themselves in these two quadrants might add the phrase “and they deserve it” to their description of their actions.

6.

It is important to realize that *each* of these quadrants (and their synthetic meeting points) are pathological. Following Fisher’s analysis, even revolt/revolution (which feels like it should be a way ‘out’) has been “pre-corporated” back into system maintenance. None of these responses (repeat, retreat, react, or revolt) offers a solution to the situation of reproduction without natality. Instead, each response palliates the situation, creating an affective release, while the structures that cause us the emotional pressures remain unchanged.

There is more to say about all this, particularly regarding the implications of the pathology quadrilateral, but I will save that for a later essay. For now, I welcome your feedback and thoughts. Is this useful? I am grateful for your input.

Jackie Wang, Carceral Capitalism, Semiotext(e) Intervention Series (South Pasadena: Semiotext(e), 2018), 107.

I need to read this a second and third time. I don't have the background in philosophy or experience in thinking philosophically to grasp this easily, but I'm willing to put in the work because this is valuable stuff. Thanks!