Nonviolence is (not) a tactic

A reflection on grammar and world building

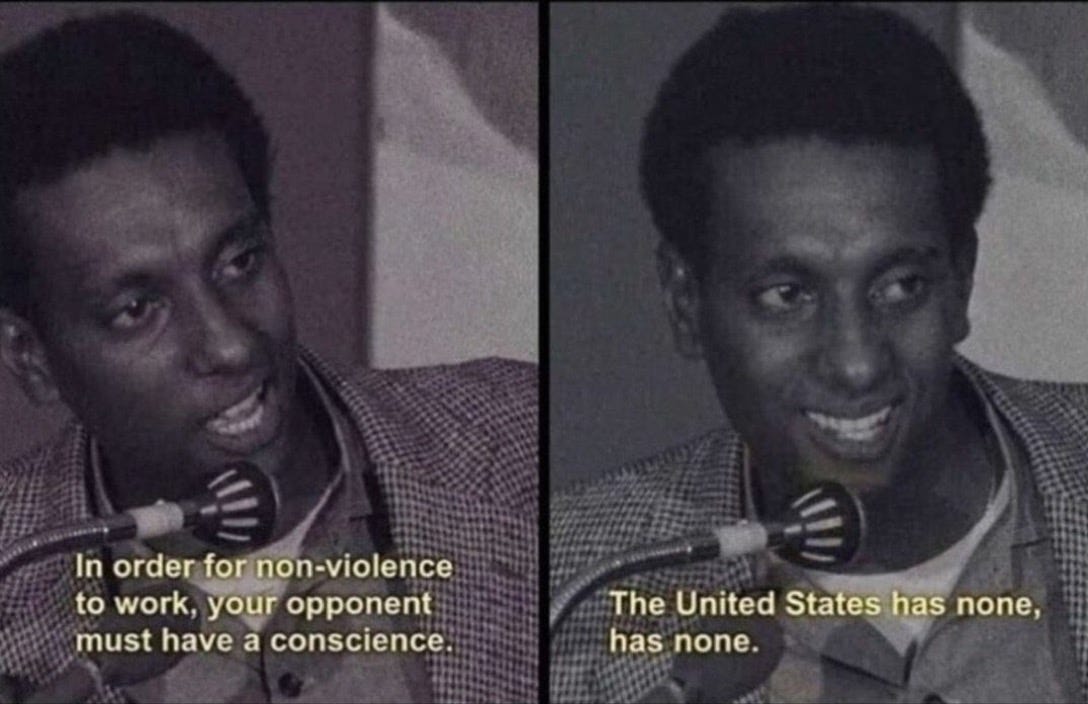

So the impetus for this essay is a quotation from Kwame Ture (who at one point was known as Stokely Carmichael), that is reflected in the image above. You can see the quotation in its more full context here. Ture offers here a double criticism in his statement. First, and clearly, he is critical of the culture of the United States, declaring it to be a community bereft of conscience. Almost sixty years on now, from Ture’s words, we should take that criticism very seriously, because it is clearly still true. At a social level, your average white American appears, by all available evidence, to be a sociopath. Meaning we will find almost any reason, however flimsy, to abandon our neighbors. Here Ture has given us a head start of six decades to work on that, or even attend to it, and we (we white folk) are still doing our same old, same old.

The second part of Ture’s critique, of course, is for the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Ture suggests that King’s nonviolence was “very good,” but it was hampered by “one fallacious assumption,” which leads us into the quotation above: in order for nonviolence to work, your opponent must have a conscience.

Your opponent. The phrasing caught me up short, when I heard it. And the language here is not unique to Ture. King himself spoke of opponents, and referred more than once to nonviolence as a weapon. Thus we have articulations of nonviolence, by no means fringe in their position, that characterize nonviolence as something you might have in your arsenal, as opposed to (and here perhaps this position is the one we might call fringe) the idea that nonviolence might mean having no arsenal at all.

All to say, Ture’s remark got me thinking. So I’m thinking, here at the start, about what it means to to imagine that nonviolence is something that you do to your opponent. I am thinking of what it means to practice nonviolence in a situation where you imagine you have opponents, and what it might be like to practice nonviolence in a situation where you get your imagining to the point that there are no opponents.

Violence as organized abandonment

In a recent essay, I suggested that “violence is a way that we materially organize spaces and bodies.” Drawing on the writings of geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore, we move away from the more “plain sense” meaning of violence (the visible kind, like when somebody gets hit over the head with a club) and begin to think of violence in a somewhat loose and unfamiliar way. For Gilmore, David Harvey, and other theorists (like me) the way to think about violence is as an organization of abandonment that aims at premature death.

This means that violence is not restricted to that visible blow on the head. Elevated cortisol levels, or stress that leads to chronic illness, or a food desert that increases the risk of heart disease and diabetes in a community, these are all seen as forms of violence. In this sense, violence are those events and patterns that point to what we Catholics sometimes call a culture of death. It follows, then, that those events and patterns that move in the opposite direction, toward what we might call a culture of life, and even what Jesus called life in abundance, point us to the possibility of some state we might call (at first) anti-violence.

That is, there are ways to arrange spaces and relationships, even in the midst of a pervading atmosphere of exclusion, isolation, and abandonments that are aimed at premature death, that do not, themselves, reproduce those exclusions and abandonments. The practice of anti-violence does not simply resist violence, and goes beyond the refusal to participate in violence. Rather, anti-violence seeks in every way to resist even the casual structures that make the perpetuation of violence possible.

One of my favorite historical examples of this is John Woolman.

As Meshach Kanyion notes in the video, Woolman’s witness often consisted of quiet but consistent non-participation in systems of exploitation and violence, even when those systems were to Woolman’s benefit and comfort. Woolman spoke and wrote against the institution of slavery, but he also refused to use products that were produced through slavery. He also refused to receive the hospitality of those who owned enslaved persons—even preferring to sleep outside in the cold, if necessary.

For many years, Woolman dressed in what was, for his time, an odd style. All the clothing he wore was grey. This was not some idiosyncratic fashion choice, but rather a recognition that the clothing dyes used in his time were brought over on the same ships that carried human beings as cargo. So Woolman simply refused to participate in that violence. Even though his clothes were not directly related to the trafficking of human beings as property, the near occasion of that practice was enough to have him “go in grey.” Woolman refused to participate in the practices that would reproduce the organized abandonments that are aimed at premature death.

Strategies and tactics

As I wrote in a previous essay, I was surprised to learn that the etymology of the word “strategy” is martial. It is irreducibly a military term. A strategy is what a general uses against an opponent, having looked at the “big picture” of the battlefield. When we use the language of strategy—even if that language seems very rational and comfortable to us—we are reproducing an irreducibly violent logic in our language. Like it or not, if a nonprofit organization has a strategic plan, it means they literally have a battle plan.

If all you have is a hammer, pretty soon the whole world looks like nothing but nails.

We have brought this idea of the strategic plan into the business world, of course. Being strategic is a backbone concept of the organizational and planning world. The irreducible logic of strategy is that of a zero sum game: I win, you lose. Or you win, I lose. When we think in terms of strategy, this zero-sum logic is part of the DNA. We may think of it as removed from the violent logics of the battlefield, but—like the clothing dye in the hold of the slave ship—strategy and being strategic is part of the world-making that arranges spaces and relationships into organized abandonments aimed at premature death.

Violence as a tactic

Break down a strategy into concrete, actionable elements, and what you have are tactics. Within a within a larger strategy, your tactics are the steps you take to achieve the the positive resolution of the conflict, so that you are on top of the zero sum game.

That is, a tactic is that a of discrete things that I do to to you in order to achieve a world that arranges and organizes you against your will. If I am doing it right, these tactics will be deployed in an order and with a force that makes any counter-tactics you might undertake irrelevant. These tactics within a strategy are designed to eliminate your agency. Above all, I don’t want anything you do to surprise me. A good strategy locks in my preferred future and locks out your preferred future.

With my strategy I wish to achieve a world where you are ordered against your will, and the world is ordered according to my will. And so any tactic that I use is going to be aimed towards the ultimate reduction of your agency in the world, because I have to win, and you have to lose.

At the same time, you are doing the same thing. You have a world (that doesn’t exist yet, but it is there in your mind) that you want to enact. This world involves me not being able to do what I want, and you being to do the maximum of those things that you want.

And you and I are constantly deploying tactics to do that.

Notice, of course, that my successful tactics lock you out of your agency and away from a future in which you can flourish. To realize my strategic goals is to lock out your strategic goals. I submit to you that the logic of the tactic is, irreducibly and by its very nature, a logic of organized abandonment. When I get my resources, you don’t get those resources, and vice versa.

In addition to having violence (de facto or de jure) occur as a result of trying to use tactics and strategies, we can also readily point to instances where violence itself has been used as a tactic toward a larger strategy of world-arrangement. A police action, a forced hunger regime, tear gassing a demonstration, or drone striking a wedding are all means and methods of sending a message to our opponents: “The world is not big enough for the two of us, and we are not fucking around.”

Again, using my idiosyncratic language borrowed from Gilmore, the atmosphere of violence, or (again, as Catholics call it, the culture of death) is the overall reproduction of a system of interlocking organized abandonments that aim at premature death. Like all organized institutions, this one takes on a kind of fictional life, and as such we can imagine this fictional life (like all living things) seeking to preserve its fictional life into a future.

Violence as a strategy

It’s easy to understand that violence is a strategy, because the organizational logic of violence fits so neatly into this etymology of the word ‘strategy.’ Violence, strategy, and tactics lock together as symbiotes. So, to achieve our desired futures, we will utilize organized abandonment in order to achieve a world where you are starved of resources, and I have all the resources. We will craft a series of organized abandonments whereby you cannot move, and I will have the maximum movement possible. If my strategy is successful, we will achieve a situation of organized abandonments, whereby you can no longer have children, and you cannot reproduce the world you desire, and I can have as many children as I want, and I can readily reproduce the world I desire.

However you slice it, it’s easy to see how violence becomes strategic. Moreover, in being strategic ourselves, we are reproducing not just the immediate action of violence, not just the immediate effects of our organizing abandonments to limit and starve our opponents, but we are creating a regime of organized abandonments that will persevere over time.

Violence, then, is the goal (a world where I and mine have access to abundance and life and where you and yours are trapped without agency in a regime of limited resources designed to lead you to a premature death). Violence is the strategy to meet that goal, and the tactics that we use to manifest this strategy are also violent. Little organized abandonments grow up to be big organized abandonments. Momentary organized abandonments and momentary arrangements towards premature death grow up to be big and constant arrangements towards premature death.

Let’s be fancy and call it a synecdoche of violence within violence. In the logic that says violence is a tactic, those tactics build up over time to a strategy of violence that eventually organizes a world of violence, organizes space and organizes bodies so that I get everything and you get nothing. Or it organizes affairs so that you get just enough to survive, a bare life, and I get to siphon off all of the excess from you, such that I get to thrive.

So these are the ways that we can think of violence as a tactic and violence as a strategy in this (admittedly, rather loose and experimental) discussion.

What is nonviolence in a given context?

If what we’re talking about is violence as a way of ordering a world, then it is ordering the world towards zero sum games and abandonments. If both the tactics and the strategies we are using to defeat such an ordered world nevertheless are part of the logic of the reproduction of that world, then where does nonviolence fit into that?

I recognize the previous sentence was convoluted. What I am trying to get at is another way of understanding Audre Lorde’s cryptic but important admonishment that the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. Again, I have written about this subject recently, trying to better understand it. What I am trying to sort out is the ways that nonviolence, as a practice in a context that assumes conflict as the ground state, cannot help but reproduce violence, even as it opposes violence superficially.

This brings us back to Kwame Ture, and the idea that nonviolence “requires your opponent to have a conscience.” I submit that this is a model of nonviolence that, strangely, only makes sense within an ongoing and reproductive regime of violence. That is, Ture (and, let’s be clear, not only Ture, but also Dr. King himself) seem to assume the continuation of ambient violence, within which the practice of nonviolence is designed to, let’s say, provoke a spectacle. That is, this nonviolence is designed to be legible within the background of violence, a contrast to highlight the violence for an audience, who will then (by grace of their individual and collective consciences) be moved to act. Spectacular nonviolence requires the continued existence of a regime of violence to remain effective and relevant.

Following Ture’s logic here, nonviolence is something I am doing to you, in order to change something about you. In this view, nonviolence is something done to the police and other enforcement authorities, in part to invite them to amplify their violence. More than this, however, nonviolence in this view is also something done to the viewer, who is sitting in relative comfort, far from the site of direct and visible violence. In this sense, spectacular nonviolence is a practice designed to alienate the comfortable from their comfort.

So let’s return to Ture’s criticism of King here. Ture suggests that, in seeing the spectacular nonviolence on their TV screens, the consciences of the comfortable would interrupt their comfort and move them to discomfort, and that distant discomfort would move them to action. Ture criticizes this by suggesting that these distant viewers have no conscience. Perhaps. But it is also possible that America (and all that American media culture provides) had found, and has found, ways to comfort the distant viewers even through the buffeting pangs of their conscience. Comfort them, or numb them, or both. If the distant viewer is moved to think “that is terrible,” that is important step. Yet if their next thought is, “but what can I possibly do?” then the system has tidied up the mess. The violence has reproduced itself in the preservation of our distant comfort at all costs.

Can nonviolence be a strategy?

Nonviolence is strategic when it is deployed to win the conflict. In this sense, as a representative of state violence, or as a distant comfortable viewer, nonviolence is something being done to me by the nonviolent strategist. In this context, the success of the nonviolent strategy depends on the response of the factions being targeted. If I do a nonviolence to you, and you do not change, then my nonviolence has failed. That is, we would consider it a bad strategy.

Forgive me for staying with the martial metaphors, but what does successful nonviolent strategy look like? It is a condition where we win all the battles, but lose the war. That is, all of our nonviolent tactics might align with a very successful nonviolent strategy that completely makes the atmosphere of violence subside from visibility. That is, those who would still wish to do violence no longer feel at liberty to enact their violence overtly or visibly. Many might consider this a win, and certainly, from the zero-sum logic of strategy itself, it is a win. My “opponent” has been immobilized. Even more, my “opponent” might feel terrorized to the point of isolation. From the standpoint of spectacular nonviolence, this is a positive outcome.

However, so long as we are still thinking in the language of strategy, there remains an irreducible violence behind our nonviolent spectacle. If we still are thinking of the nonviolent as “the righteous,” and the violent as “the opponents,” we remain trapped in the zero-sum logic of conflict. This may be the best that strategic nonviolence can offer us.

Nonviolence as a tactic

Our experience with nonviolence in the various contexts it has been deployed has been, on the whole, a tactical nonviolence. That is, it has been deployed in a context where the grammar of violence governs all the sentences that are uttered, and all the actions that are taken. In this sense, most nonviolence we have observed does not even rise to the level of strategy. Rather, nonviolence has been used in a piecemeal fashion, to varying effect.

When nonviolence is deployed primarily as a tactic, its core intent is to use violence against itself. As a spectacular tactic, it seeks to make the existing violence more pronounced and more visible, to the point where the continuation of violence seems brutal or absurd to distant viewers.

In this sense, spectacular nonviolence is primarily an exercise of public relations. It seeks the exaggerated contrast of the violent context and the visible nonviolence of resisters to cut through the background noise of the media marketplace, to reach the eyeballs (and, pace Dr. King, at least according to Ture) the consciences of the comfortable distant viewers.

Certainly, at the same time, those who seek reproduction of the violent system are also using violence itself as a PR tactic. Those who wish to preserve the regime of violence want that violence to feel ambient to the comfortable distant viewers. This ambient violence has a number of layers. There is a layer where the violence adds to the comfort of the distant viewers (“The police are here to protect us and preserve our way of life”). At the same time, the violence quiets the distant viewers (“I better not do anything to get in trouble. I don’t want to end up like them”).

Therefore, those who use tactics of spectacular nonviolence are playing with a double-edged sword (again, I am framing this in martial terms intentionally). They are hoping that their public actions of nonviolence will pull the violence into the media landscape in a certain way, a way that will move the viewer to abandon their comfort for the sake of conscience. Yet in doing so, they also risk that the narrative that the distant viewer sees is one that is solely framed by the grammar of violence. As Ture points out, this may be too high a risk to take.

Using (non)violence to frame a narrative.

Is nonviolence something that I do to you? Does your response to my nonviolence matter? This seems to be Ture’s position. Like violence itself, nonviolence can be a tactic for achieving a strategic outcome in an ongoing zero-sum struggle. To the distant, comfortable observer, violence tells a certain story.

This story is an easy one to tell at a distance, to the comfortable observer, because it is the frame of almost every story we tell in our culture. We are used to hearing the story that violence is the solution to our social problems and even our casual misunderstandings. Characters not only hit (and shoot) each other, but they routinely withhold the truth, offer limited options, and limit the agency of other characters. No wonder we grow up thinking that this is the story that applies to all our disagreements and all our problems.

If violence frames our story, then nonviolence becomes a tactic within that frame of violence. Even if it serves to delay the overt violence in a given moment or a given place, nonviolence framed in this context does not and cannot escape the perpetuation and reproduction of violence. If nonviolence is something I am doing to others, then it fits neatly into the martial logic of strategy.

But what if nonviolence is something I am doing with and for myself, instead of to others? What if, instead of delaying atmospheric violence, this nonviolence is building a world where I truly can be in community with others—even those who have been declared to be my “opponents”? Is there a story that doesn’t involve this zero sum logic of of organized abandonments and premature death? This seems, to me, to be the primal and primary question—a question that precedes the grammar of violence. Again to use the wisdom of that line from The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, “Before you choose, decide!” Decide that you will operate in a different story and a different world than the one defined by violence that has been tuned for the entertainment of the distant, comfortable observer.

What then would be a non-strategic form of nonviolence? What would it mean to remove our nonviolence from our arsenal of tactics? Can we even imagine such a shift? What would it meant to remove our nonviolence from the logic of the generals surveying a battlefield? What would it mean if our nonviolence ws no longer part of the reproduction of a world of organized abandonments?

If we’re not participating in the reproduction of strategic outcomes, what kind of world are we building? Are we building a world that is, in some way, composed of little actions that lead to a strategic outcome? Are we building towards a known and predictable end, or are we building towards surprise?

I think the answer is we are building toward surprise.

In that case, nonviolence cannot be a strategy. It cannot be a tactic. Nonviolence in a non-spectacular, non-strategic sense must interrupt the reproduction of the world whose grammar is violence, and whose currency is the organization of abandonment. With this shift, nonviolence is no longer something that I am doing to you. It cannot be. Nonviolence is no longer predicated on your response. It cannot be.

Kwame Ture, it seems, can only imagine the success of nonviolence to the extent that it will change his “opponents.” My suggestion here is rather a nonviolence that shifts my own perception to the level that I no longer perceive my fellow-beings as opponents. The nonviolence I am suggesting is a refusal to live in a zero-sum world.

This alternative configuration of non violence understands that it has nothing to do with the actions or responses of my “opponents.” Rather, it has everything to do with how I choose to live in the world, and how I reproduce that world through my actions (as well as my refusal to take certain actions).

Nonviolence as a form of worldbuilding

This form of nonviolence is not an inability to do violence. The nonviolent are not impotent. It’s also not an inability to imagine violence. In fact, it is because the nonviolent can clearly see in their mind’s eye the horror of violence that they are so keen to steer the world in a different path.

Yet we must recognize that violence is presented to us, even sold to us, with the assurance that it is the most efficient means to reach our (strategic) ends. Violence is presented as clearly bing more efficient than discussion. If I can terrorize you or imprison you, then I don’t have to worry about navigating any surprising or unexpected outcomes you might create. A violent world eschews inefficient methods and inefficient (or simply inconvenient) persons. Such a world is continually reproduced because the inhabitants of that world have been assured at the most basic level that the reproduction of violence is the most reasonable, most efficient option.

In a context where imagining and enacting violence is the most reasonable option, the person committed to self-transformative (rather than spectacular) nonviolence will choose the unreasonable option in the world. Where enacting and imagining violence is the most efficient means that the world offers to me to achieve my ends, I will choose inefficient means. I will make the conscious decision to limit my own effectiveness in the world for the sake of reducing the violence experienced in the world.

And I will do this not because I am wanting some outcome from you, or I am wanting to impose some outcome on the situation, but because the world that I wish to live in will be a world where I will not have harmed another, where I will not have participated in arrangements of organized abandonment, and I will not have participated in the logics of premature death. I will not have reproduced the zero sum game, thinking that because I’m the one reproducing it, it somehow will produce a more moral or more righteous result than if someone else reproduces it.

I will instead try and stop the reproduction of the zero sum game entirely, to interrupt the grammar of violence, and I will try and build a different world.

Nonviolence is (not) a tactic

So non violence is not a tactic—at least, not in this sense used by Kwame Ture above. In Ture’s sense, nonviolence can be a tactic that is either efficient or inefficient in reproducing a world where people like Ture are on top. Ture might think that such a state of affairs would lead to a better world, with “better” outcomes. But this path (the path of spectacular or even coercive nonviolence) is not leading us out of the cycle of violence offered by the present world. Spectacular, coercive nonviolence inadvertently reproduces the world of exclusions that it claims to wish to abolish.

What it would mean to practice nonviolence in a manner that does not depend on our “opponents” having access to their conscience? What if there is a practice of nonviolence where changing the other is no longer the metric?

If we take this latter path, it seems to me we’re no longer “doing” nonviolence as a tactic. We’re not depending upon the United States being moral, and we are no longer expecting our “opponents” to respond to our non violence in a positive way. Rather, our nonviolence is about the task of building a different kind of world, a world that cannot be measured by the strategies or the tactics of this present world.

Self-transformative, non-spectacular, non-strategic, non-tactical nonviolence is an eruption and an interruption. It is a prior commitment, that manifests before the grammar of the present age. it is no longer defined by or confined to be to a reaction to the violence that is is imposed upon a group. Rather, it is a form of action in and of itself, an action hiterto unanticipated by the zero-sum logics of this world.

The Civil Rights Movement sent children to the lunch counters and into the streets, knowing that they would get spit on, arrested, and sprayed down with the fire hoses. They sent the children into these spaces because they understood that the images that would then be beamed out to the world would serve as a spectacular form of nonviolence. This tactic was calculated for efficiency, on a cost-benefit scale, and the risk (to the participants, and the risk of reproducing a zero-sum world) was deemed to be worth taking.

Unlike Kwame Ture, I have zero criticism of the civil rights movement for that calculation. At the same time, six and seven decades on, I must ask—in all moral seriousness—what good those nonviolent tactics achieved, in terms of lessening the violent logics of the world, because, good God, look around us.

So I think I am looking for a different form of nonviolence. I am seeking a nonviolence that is neither a strategy nor a tactic, but rather nonviolence as a form of failure. I borrow this term from Jack Halberstam, and his book, The Queer Art of Failure. The book has a lot to say about production, reproduction, and failing to reproduce certain behaviors, attitudes, and worlds.

The nonviolence I have in mind takes the form of failure because it can no longer be measured on the metric of “winning” or “losing.” It is no longer grasped by the grammar that suggests that some of the fellow-creatures we encounter are our “opponents.” It builds a new world in the most inefficient manner possible, by failing to live and reproduce properly in this one.

This self-transformative, non-spectacular nonviolence shows a way. It shows that there can be an agency involved in opting out of the violent system entirely, in saying (in the language of Bartleby the Scrivener’s “I prefer not to”) I will not: I will neither use the violence you offer me, nor will I react to it. I will imagine and live differently, and it has nothing to do with you or my changing you. It has everything to do with how we live with ourselves, and live with others, and how we choose to build and enact community.

What I think I am pointing to, finally, is what I hear in Fr. Greg Boyle’s vision when he says there is no “us” and “them”—there is only us.

I recognize that this essay is both long and disorganized. I am really trying to get at a set of ideas that are still somewhat jumbled in my head. It would be a great benefit to me if you would think with me. That is to say, please post your reactions and thoughts—especially if you spot my blind spots or places where my thinking here can be improved. As always, thank you for taking part in this ongoing conversation, however you choose to engage. I truly appreciate it!

Thank you. I'm going to think of Jesus' parables and teachings with this in mind. Loving my neighbor as myself, the vine and branches, who is my neighbor, you say that I am a king. Jesus lived among us to show us the fallacy of the zero sum game.

I experienced your essay as 'long,' but not as 'disorganized.' Sorry I can't offer more than that. Thanks for thinking through it. You've made explicit for me an issue with nonviolent 'tactics' that I've felt for a very long time but haven't known what to do with.