On strategies, principles, and tactics

If you know your history, then you will know where you're coming from

1.

Recently I was surprised to learn that strategy is a martial term. That is to say, if you trace the word back to its origins, its DNA is military, through and through. The earliest root of strategy is the Greek stratēgos, an army leader. The stratēgos was the one who could see the whole battlefield, and who could think beyond the immediate moment of battle to comprehend the “bigger picture.”

Nowadays, of course, we apply the idea of strategy to all manner of social arrangements and business ventures, not just to warfare. But I suspect that some aspect of that DNA remains, no matter how much we alienate the term from its original source. To have a strategy, to be strategic, implies that there is a goal to be accomplished, a prize to be won. And where there are winners, naturally there are losers, as well.

Strategy is part of the logic of the kind of world that is governed by the iron law of the zero-sum game.

2.

One thing you learn if you hang around business types is that one does not ever engage in strategy alone. To have a strategy requires at least one other, even if that other is merely “my adversary” or “my obstacle.” A strategy requires something to be gotten past, a kind of final boss battle. Strategy invites us to think big, go big, swing for the fences.

At the same time, all my business friends will remind me that it is certainly a fool’s errand to try to accomplish a strategy all at once. To be really effective, to really do the whole strategy thing, one must break it down into bite-sized chunks. A grand strategy is made up of any number of component strategies. These smaller components are tactics.

Like strategy, this word “tactic” has an ancient Greek source: takitē. Back in the day, takitē meant “the art of arrangement.” This arrangement was very often military in character, so once again there’s that martial DNA, connecting the tactics to the strategy not only by their shared context of how one approaches a battlefield, but also there is a semantic entanglement here. To have an effective strategy, one must have an effective set of tactics. Moreover, for any set of tactics to “make sense,” the set needs to reside within some larger context of the grand strategy. Orphaned tactics are just so much empty motion.

3.

All this came to mind a couple weeks back as I was watching this short “explainer” clip from historian Heather Cox Richardson. In the video, Richardson is pulling apart the logic of “gerrymandering” as a kind of grand strategy.

Richardson notes that the Republican party has resorted to ever-more excesses in regard to drawing district lines for representation. The result is that a great number of citizens have been effectively disenfranchised.

In the present discussion, then, we might say that disenfranchisement if the strategy, and actions like voter roll purges are tactics. They may be tactics undertaken for all the “right” reasons (i.e., the administrators employing the tactics might be convinced “true believers” in their particular cause or narrative about the upcoming elections). Nevertheless tactics are ultimately judged by their effectiveness. This is to say, tactics are ultimately judged (and evalauated) with an eye toward how well they move the situation to an ultimate goal (again, that goal is defined by the strategy.

So, in the case of Heather Cox Richardson above, the strategy she is proposing is a campaign to “fight back” against Republican gerrymandering using the tactics of Democratic gerrymandering.

4.

Now before we go accusing the Democrats of being hypocrites, (which they may in fact turn out to be; time will tell), we need to understand that tactics are not judged on their own merits, but only can be judged in their utilitarian relation to the strategy.

Under this logic, then, Republican gerrymandering (which aims at a strategy of voter suppression and election-rigging) and Democratic gerrymandering (which aims at the eventual re-enfranchisement of vulnerable populations) are completely different activities. And they are different even as they are exactly the same (a weirdly-drawn district is a weirdly-drawn district, after all).

But no, the locus of judgement here is the strategy. And in service of that strategy, it is often the case that “anything goes” with regard to tactics; or, at least, we might say “all’s fair.” If the strategy is righteous (at least from a certain perspective), then there is no way that a given tactic might be unrighteous.

I imagine some of you are chucking a bit at this point.

5.

What’s so funny? What’s funny is that any fifth grader could spot the trouble here. A fifth grader and a Catholic moral theologian, both, might tell you that the ends (that is, the strategy) can never justify the means (that is, the tactics). Under this watchful eye of the superego, its heralds will tell you that it is better to lose nobly than it is to win ignobly.

And of course, Democrats have been losing nobly for a while now.

So Heather Cox Richardson here is calling for a set of tactics that will help to ensure that an overall Democratic strategy (which, one assumes, she perceives to be superior to the Republican strategy) will prevail. At this point, furthermore, it must triumph by any means necessary. Richardson is not willing to submit the goal to a principle.

6.

Where the roots of strategy are Greek, and point towards ends, the roots of principle are Latin, and they point us towards foundations and beginnings. Your principles are the things you have well in place before any battle or contest begins. The principle is that mechanism that allows you to discern the difference between the Republican and the Democratic strategies, even as they use the same tactics.

The logic of principle is well summed up in a line from the band Genesis and their album, The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway. In the song “IT,” near the end of the album, the listener is admonished with the cryptic command: “Before you choose, decide!” This is to say, a principle is a commitment that comes before the decision, and even perhaps before rationality itself. Your principles will limit for you even what counts as reason, as reasons, as reasonable.Your principle is the foundation upon which the edifice of actions is built.

7.

I will have more to say about these matters, including a much longer essay I’ve been working on for a couple of weeks that expands on several of the concepts above. For now, though, I think a good “basic idea” is in place, and I will leave things here.

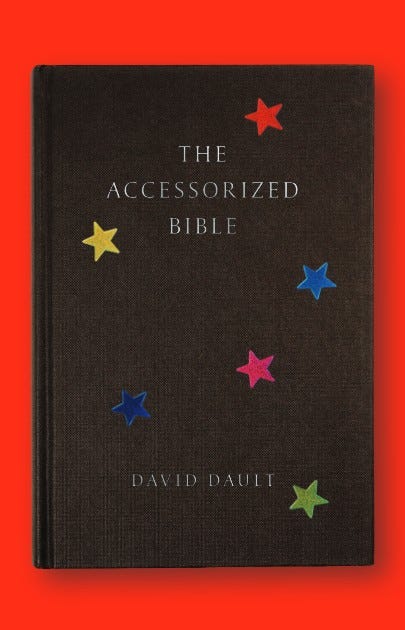

A quick aside to say that my new book, The Accessorized Bible, due out in mid-January from Yale University Press, has just passed a significant milestone on the way to publication: It now has a cover:

If you would like more information about the book (and I hope you will!), you can find that here. Thank you.